Social interaction shapes and boosts second language learning: virtual reality can show us how

The first time you heard someone say “Careful!” in a foreign language that you were trying to master (hereafter referred to as a second language (L2)), this utterance was likely framed by a series of multimodal cues, such as feeling a stranger grab your arm and seeing a bicycle racing towards you. These complex environments enriched by social contexts and physical cues are a far cry from the flat-screen paradigms that are generally used to examine L2 learning and processing. This discrepancy mirrors the diversity of real-life L2 learning contexts, which range from interactive and immersive to rigid and textbook-based. Learners also differ in how they approach L2 learning: some are prone to gather knowledge and learn from social interactions and personal feedback (social or communication-oriented learners), while others favor more analytical and non-social forms of learning1,2,3. Importantly, practicing an L2 in social contexts is thought to be particularly beneficial for reaching a high level of proficiency4,5,6. Indeed, no matter how much learners are exposed to an L2, if they do not engage in social interaction, attaining proficiency is nearly impossible7,8. And, undeniably, most language learners aim to use the target language in meaningful exchanges5. Across disciplines, momentum is building to integrate social reality into models of language processing and L2 learning6,8,9. With all this in mind, we believe it is crucial to consider how social processes affect L2 learning.

We begin by reviewing in-depth multidisciplinary theoretical approaches and studies that have investigated how social interaction can support L2 learning. We then examine four key components – multimodality, embodiment, interaction, and feedback – and consider how each supports L2 development. Next, we turn to recent neuroimaging studies that shed light on the neural mechanisms underlying socially interactive L2 learning, while highlighting the persistent trade-off between ecological validity and experimental control. To illustrate how these mechanisms might operate in practice, we present word learning as a case study, focusing on how socially grounded contexts may enhance lexical encoding and integration. Finally, we review the potential of using virtual reality (VR) simulations as a promising methodological tool for advancing research on how social factors shape L2 learning.

Socially interactive language learning: theoretical frameworks

Studies examining the cognitive processes underlying language acquisition have traditionally focused on infants and children10,11,12. Even before children can utter their first words, language is learned not only through exposure but through active participation as facilitated by social interaction13. As such, language acquisition theories and models emphasize the importance of social cues in developmental language learning. From a social-pragmatic perspective, communication motivates language acquisition, and interaction results in learning14. In particular, social interaction is thought to expedite referential learning by engaging sensorimotor and attentional mechanisms15,16. Indeed, joint attention, or shared attentional focus between two individuals (e.g., a caregiver and a child), such as when playing with a common object17, has been associated with facilitated language learning (i.e., word segmentation18, semantic integration19). Language development is also tightly linked to parental responsiveness, or well-timed, relevant responses to infants’ attempts to explore and communicate20. A social behavior21, parental responsiveness is both temporally and conceptually connected to the learning environment, which is thought to support word-to-referent association20. For instance, communicative feedback – informing children whether their utterance has been understood – is a particularly effective element of communicative coordination during language development13.

Compared to children, adults are thought to learn a second language in a more conscious and deliberate manner, with outcomes shaped by factors such as linguistic background, motivation, cognitive abilities, and other individual differences. Still, since the foundations of language learning are established early in life, it is reasonable to think that some of the same socially grounded mechanisms may continue to influence learning well into adulthood. Drawing parallels between first language (L1) acquisition and socially interactive L2 learning enables the exploration of how key factors in L1 acquisition (i.e., joint attention and communicative feedback) may also support L2 learning, thereby enriching our understanding of language acquisition across different contexts. As has been suggested for children14, successful adult L2 learning could be grounded in social interaction15. However, translating socially grounded frameworks into controlled experimental paradigms remains challenging. Traditional lab tasks struggle to capture the dynamic quality of real interaction, making it difficult to isolate the specific contributions of mechanisms like joint attention or communicative feedback.

While insights from L1 acquisition provide a valuable foundation for understanding the social basis of L2 learning, the field of Second Language Acquisition (SLA) has developed its own rich theoretical landscape. Drawing from a number of disciplines, including linguistics and psychology, SLA has long emphasized the critical role of socio-cultural factors in L2 learning, particularly how its underlying processes can be elucidated by language production and comprehension5. In the 1960s, anthropological linguistics and sociolinguistics contested the then-popular Chomskyan view, which framed language knowledge as a competence/performance dichotomy, and instead viewed language as a form of communicative action to be learned in situ22,23. Another important influence for SLA was Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory24, later extended to L2 learning25,26,27, which claimed that meaningful interaction is at the root of how we learn. These models generally converge on the idea that consistent and meaningful language practice results in L2 proficiency5, emphasizing the critical roles of both the quality and quantity of language input and learner output in the L2 learning process28. For example, corpus analyses reveal strong links between the amount and type of input and learners’ L2 development and performance5,29. Further, longitudinal case studies using conversational analysis revealed how social contexts shape L2 learning trajectories30, often observing changes in how learners use social cues (i.e., gaze, gesture, or posture) as learning progresses17,18,31,32. Indeed, social interaction is both a medium for practice and a catalyst for the eventual automatization of language skills33,34,35 in contexts ranging from study abroad36 to task-based classroom interaction37.

Building on these theoretical foundations, a key question is: what specific mechanisms make social interaction so powerful for L2 learning? Li and Jeong38 recently proposed the Social L2 Learning (SL2) model, based on L2 learning with social interaction, defined as “real-life or simulated real-life environments where learners can interact with objects and people, perform actions, receive, use, and integrate perceptual, visuospatial, and other sensorimotor information, which enables learning and communication to become embodied”9. In line with previous models39,40, this approach claims that L2 learning processes only differ from L1 acquisition because L2 learning contexts are generally poorer. Furthermore, the Social L2 Learning model bases its premises on memory research, pointing to the interdependence between encoding and retrieval processes. For instance, according to the encoding-specificity principle, retrieval of learned content is facilitated when learners are in the context in which they first encoded semantic information41. Interestingly, learning conditions could have an important influence on which memory processes learners use, as individual differences in declarative and procedural memory capacity predict L2 learning42,43. Menks and colleagues44 posit that classroom instruction calls more upon the declarative memory system, whereas immersion-like learning is likely to involve the procedural memory system. This could, in part, explain the social advantage for L2 learning and aligns with the view that implicit learning facilitates automatization33. Nonetheless, as noted by Bowden & Faretta-Stutenberg45, opportunities for interaction vary considerably across cultural and classroom contexts, and many modern L2 classrooms now promote meaningful social interaction.

These interdisciplinary contributions converge on the view that language learning emerges through active, socially embedded communication. Each framework brings valuable insight into how social interaction shapes L2 learning, yet they leave open questions about the specific mechanisms involved. We argue that advancing the field of second language learning calls for creating a unified account of how social interaction shapes L2 learning. For this, future research must more rigorously isolate, manipulate, and empirically evaluate the processes that each framework identifies as central to successful L2 learning.

Second language learning in social contexts: important factors

The previous section outlined the theoretical foundations of socially interactive L2 learning. We now turn to key mechanisms through which these interactions support language development. In particular, we highlight four core factors – multimodality, embodiment, interaction, and social feedback – that recur across frameworks and could play a central role in L2 learning.

Multimodal learning engages more than one sensory modality, such as receiving both auditory and visual input while listening to and watching someone speak. Here, multiple channels of information can enhance comprehension and solidify knowledge by tying learning to physical and social cues. Multimodal cues are intrinsically involved in a real-world language comprehension and production, and should hence be examined in L2 learning, including in naturalistic social contexts46,47. Visual cues, often present in learning environments, can facilitate learning by enhancing the complexity of formed representations48. Encoding new words with images, for instance, improves learning compared to verbal learning alone or learning with translations49,50. On the premise that language is a “a system of communication in face-to-face interaction”51, engaging in social language use involves exposure to rich visual and auditory human-produced cues that provide critical contextual information, which enhances comprehension and supports more effective communication. Indeed, multimodality facilitates language comprehension52,53, with auditory cues such as prosody54,55 and visual cues such as gestures56 helping us to contextualize spoken language.

Two recent studies presented behavioral and electrophysiological evidence that mouth movements, gestures and prosody operate dynamically to facilitate word predictability in the L153, and, to a lesser extent, in the L257. This approach increases ecological validity by observing how co-occurring multimodal cues are used interactively during language processing, as opposed to only manipulating cues in isolation. Together, this evidence suggests that multimodally enriched learning strategies boost language comprehension and retention. In line with Zhang and colleagues’53,57 and De Felice and colleagues’58 studies, L2 learning research would benefit from further examining whether and, if so, how different multimodal social cues affect processing and encoding in closer-to-life, social situations.

Embodied theories of language emphasize that in addition to engaging multiple sensory channels, socially interactive language learning is also grounded in physical and sensorimotor experiences. From this view, linguistic representations are shaped by our interactions with the surrounding environment and grounded in real-world, experience59,60. Embodied or situated learning implies being physically present or involved in a learning context61. Physical action, whether it be manipulating objects62 or performing gestures63,64 has been shown to support word encoding via the activation of the motor system, forming “motor traces” that strengthen semantic representations. There is a substantial literature showing that learning new words while performing gestures leads to improved learning, compared to learning with pictures or using standard rote verbal learning49,64,65. Furthermore, performing spontaneous gestures not only helps speakers to communicate66 but is thought to support L2 learning67. Interestingly, simply observing gestures or actions that are congruent with the meaning of words being learned enhances L2 learning68,69,70,71. This indicates that embodied processes, as induced by action observation, support learning even in the absence of physical interaction. Pertaining to embodied language encoding facilitations, it has been suggested that, on a neural level, the association of spoken words to images or gestures links semantic concepts to visual72 and motor areas73.

Interactive Learning occurs when learners actively engage with their environment, whether by manipulating objects or interacting with a partner, which plays a crucial role in language learning. Whereas multimodality and embodiment can be considered separately from interaction, the opposite seems nearly impossible. For example, at the crossroads between embodied, multimodal and interactive word learning, simply holding objects has been shown to aid in L2 learning74. As for social interaction, one study had participants learn conceptual information about novel lexical items while observing social content compared to engaging in online social interaction58. Seeing the teacher’s face resulted in improved learning, but only during interactive learning, suggesting that different mechanisms subserve interactional vs. observational learning processes (Fig. 1B). Therefore, while added visual and motor information appears to contribute to L2 learning in a number of experimental tasks, this multimodal advantage may be modulated by sociability. It would be worthwhile to explore whether this conceptual learning effect extends to L2 learning, where learners typically acquire new labels for familiar concepts.

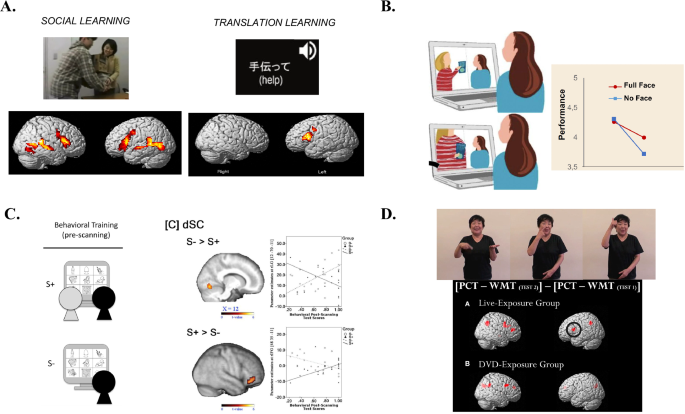

A fMRI study that compared learning L2 words by viewing videos of social situations vs. translation. Here we see the brain areas activated in each type of learning (contrast between initial and learning and the following session). Note that Social learning shows greater activation in the right middle temporal gyrus, the superior temporal sulcus, and the inferior frontal gyrus, and both conditions show greater activation in the left inferior frontal gyrus, and supplementary motor area (Jeong et al., 2021; License: CC BY 4.0) B Behavioral study comparing learning conceptual information about new words by observing (Recorded) vs. engaging in (Live) social interaction. The Live condition resulted in greater behavioral accuracy post-training overall. Viewing the teacher’s full face improved learning in the Recorded condition but not in the Live condition (De Felice et al., 2021; copyright permission from Elsevier, license number: 5812910454464) C fMRI study comparing L2 learning with an imagined social partner vs. a computer. A positive correlation emerged between accuracy post-training and activity in the right inferior frontal gyrus for the interactive group and in the fusiform gyrus for the non-interactive group. (Verga & Kotz, 2019; copyright permission from Elsevier, license number: 5812620564760) D. fMRI study comparing sign language syntax learning with live interaction vs. through viewing videos. Only the Live interaction group showed activation in the left inferior frontal gyrus post-training. (Yusa et al., 2017; License: CC BY 4.0).

Social feedback – broadly defined as contingent social information that learners receive in response to their language use – and consequential reinforcement can help shape and refine learners’ developing linguistic system. Corrective feedback draws learners closer to their goals by bringing attention to their errors, building declarative knowledge, and allowing them to find better alternatives via self-correction, which can impact procedural knowledge and eventually lead to automatization35,75. Affective feedback, such as praise or encouragement, could likewise play an important role in motivating learners. L2 learning conceived as a social activity might be governed by the complex rewarding dynamics involved in socialization76 and the value we assign to these interactions77,78. Not only do we prioritize social information79,80 but we treat it along with emotional content, associated with processing advantages81,82. Being liked by others activates the dopaminergic system83 and both avoiding social disapproval and anticipating social reward activate the ventral striatum/nucleus accumbens. Socially interactive L2 learning can engage multiple forms of social rewards (e.g., face attraction, gestures, subjective assigned value, positive feedback) and is tightly linked to social motivation79. During its initial stages, L2 learning is largely controlled by external feedback – a form of social reward or punishment – whereby native or advanced speakers provide performance feedback and corrections to the initial production of new utterances. The quality of this feedback (including the positive or negative emotional content) and its impact in reward-motivational systems might also affect the encoding process of new linguistic information and speakers’ motivation to pursue their goals84. Importantly, learning new words is associated with an increase in the activation of core reward brain regions (e.g., the ventral striatum85,86) and these effects are modulated by dopaminergic pathways87. An increase in dopamine has been shown to facilitate the encoding of new information in the hippocampal cortex88. In a recent event-related potential (ERP) and pupillometry study, we showed that reliable social feedback in the form of dynamic videos, compared to symbolic feedback (a static image of ✓or ✖), led to more widespread cortical activation and better differentiation between positive and negative feedback. Furthermore, social feedback had a greater overall impact on word learning, as shown by correlations between the ERP and pupillometry measures and post-training performance scores (Zappa et al., in press).

Given the above evidence, examining how social feedback can shape L2 learning as supported by reward processes could prove a very fruitful avenue. We propose that social feedback be conceptualized as both in its informative content as well as it emotional-rewarding value. Furthermore, future work should examine how individual learner profiles respond to different types of feedback (e.g., social, symbolic, encouraging, or critical). In doing so, we may gain a more nuanced understanding of how feedback shapes L2 development over time, and how its social dimension can contribute to optimizing both learning outcomes and learner motivation.

It is worth noting that although the above reviewed factors (multimodality, embodiment, interaction and social feedback) often overlap, they do not necessarily come as a package in real life, and even less so in controlled experimental studies. Face-to-face conversation involves all four dimensions, combining multimodal information (auditory and visual) with the interactive (including feedback), back-and-forth nature of dialog and embodied physical presence in a linguistic setting. Conversely, phone conversations typically lack these multimodal aspects; passively listening to a teacher is not interactive, and online interactions generally fall short of providing an embodied experience. While the effects described are compelling, most studies to date have been constrained by methodological limitations and, indeed, few have tested how these elements operate in truly interactive settings, highlighting the need for tools that can simulate authentic, multifactor, responsive environments while allowing for precise experimental control. To fully understand the contributions of these factors in second language learning, future research should test them both independently (i.e., isolate specific modalities or interaction types) and in combination (i.e., examine how they interact within contextually rich learning environments). This dual approach will clarify the mechanisms through which each supports learning and identify the conditions under which their integration produces additive or even multiplicative effects.

Neural evidence of socially interactive second language learning

Despite the growing number of studies on the role of social interaction in L2 learning6,8,9,45, little is known about the core cognitive and neuronal processes underlying L2 acquisition involving social interaction. Examining brain activity during socially interactive L2 learning and processing can give us important clues as to the efficacy of different types of learning contexts, or even learning styles. Thus, L2 research stands to gain a great deal from neurocognitive studies that unveil the processes underlying socially interactive L2 learning, including L2 processing differences that occur during or as a result of different learning strategies.

While this area remains underexplored, a handful of functional magnetic resonance imagining (fMRI) studies on adults have examined the relationship between how words are encoded (i.e., socially vs. not) and the neural activations during the subsequent retrieval of these words. For instance, words learned by viewing videos depicting social situations activated the right supramarginal gyrus during retrieval, similarly to what is observed during L1 processing, whereas those learned via textual translations activated the left frontal middle gyrus89. Furthermore, when focusing on neural processes during L2 word encoding in social vs. non-social situations as depicted by videos, the former also led to improved behavioral performance and greater activation of brain regions previously associated with social, affective, and perception-action processes during learning90 (Fig. 1A). Overall, these results indicate that encoding words by viewing social situations could lead to more native-like processing. In line with the Social L2 Learning model, it is possible that processing complex social, emotional, and action-related information in a social vs. non-social context during encoding leads to the formation of richer representations of the newly learned L2 words and facilitates retrieval during the post-training tasks. These results also corroborate the idea that multimodality, as provided by the multiple auditory and visual cues present in social contexts, can support learning. On the other hand, given that in both these studies the “social” condition consisted of participants passively viewing pre-recorded social scenes, this paradigm is limited as regards testing how embodiment or social interaction shapes L2 learning.

Another strategy used in fMRI studies to engage participants in social interaction is to scan them as they perform activities that they believe to be a live interaction15. Verga & Kotz91 used a simulated interactive context (i.e., playing with an imagined social partner vs. with a computer) to examine the effect of social interaction on L2 learning (Fig. 1C). During learning, social learners showed greater activation in the right supramarginal gyrus, associated with social cognition, similar to what Jeong and colleagues89 found during retrieval. Activity in the right inferior frontal gyrus, associated with attention, correlated with post-training accuracy for words learned in non-informative contexts, but only for social learners. From a social pragmatic perspective, it is likely that social learning helped learners to integrate new meanings via attentional processes. However, although game-playing is naturally interactive, this imaginary social partner paradigm does not provide the embodied and multisensory richness of interacting with a social partner in real time, and it remains uncertain to what extent participants believed they were interacting with a real partner. In fact, both video viewing and simulated social interaction are limited in that they do not allow for the manipulation of multimodal social cues, or the observation of how these affect L2 learning. Furthermore, the Social L2 Learning model, which argues that L1 and L2 learning differences are due to learning context, cannot convincingly be tested via these L2 teaching methods that bear little resemblance to naturalistic L1 acquisition.

Yusa and colleagues92 used direct social interaction to compare post-training brain activity in participants who learned Japanese sign language syntax with a native deaf signer to that of those who viewed instructive videos (Fig. 1D). Both groups learned through physically signing, as opposed to passively viewing the teacher or videos. These two conditions directly tested the effect of embodiment, as induced by participants in the live exposure group being physically present with the teacher, and multimodal social cues, on learning. Syntactic processing post-training led to activations in the left inferior frontal gyrus, similar to that displayed by native listeners in the live exposure group but not in the video viewing group. These results further support the Social L2 Learning model by indicating that learning with a partner could lead to more native-like processing of an L2 compared to passive observation. Future studies should extend this type of paradigm, preferably adding actual back-and-forth interaction, to examine the neural correlates of how different aspects of sign and verbal L2 learning (e.g., word learning) as well as different types of social interaction (e.g., teacher-learner, learner-learner) and learning environments (e.g., classroom, café) impact L2 learning.

The above studies all use a single-brain approach, meaning that only one participant’s brain activity was measured during the experiments, which is sometimes thought to be limited in measuring social learning (for a review, see ref. 93). The second-person neuroscience approach seeks to increase ecological validity by observing neural processes while participants engage with a social partner in a close-to-life, dynamic, back-and-forth manner94. Hyperscanning has recently been widely proposed to investigate the brain correlates of social interactions. Here, interbrain neural activity is explored via electroencephalography (EEG), fMRI or near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) recordings of activity generated – often simultaneously – by two or more brains95. Social interaction is associated with inter-brain synchrony between participants in face-to-face vs. back-to-back dialog and monologs6, during interactive vs. non-interactive object-naming and verbal descriptions96, and in successful educational dialogs97. Dikker and colleagues examined group interbrain synchrony between a group of students using portable EEG in a longitudinal, real-world classroom study. Watching videos or participating in a common discussion led to greater synchrony compared to listening to a teacher lecturing or reading out loud, which was interpreted as reflecting social interaction and underlying shared attention98. We should note that this study conflated the effects of interaction with those of multimodality. A similar “group neuroscience” study compared individual and teammate performance in problem-solving tasks. Overall, team members outperformed individuals, and a relationship emerged between performance and inter-brain synchrony within a group99. However, although dual-brain synchronizations have been interpreted as reflecting the neural correlates of social interaction, it is important to consider that this phenomenon could simply reflect low-level perceptual mechanisms involved in perceiving a common environment (e.g., auditory processing)100. Nevertheless, hyperscanning merits being contemplated as a potentially important tool for socially interactive L2 learning studies.

Overall, neuroimaging studies provide encouraging first steps toward understanding how social interaction shapes the brain mechanisms involved in L2 learning. Recent findings suggest that socially grounded encoding can lead to more native-like neural responses during word retrieval and may engage brain regions associated with social and attentional processes. However, stimuli are typically presented on flat screens, which clearly restricts our ability to capture how we learn languages in real life101. Furthermore, most have relied on the passive viewing of pre-recorded social scenarios or participants imagining social partners, thus limiting our perception of real-time, embodied, and multimodal social interactions. Finally, by dichotomizing conditions as “social” versus “non-social”, prior work has not isolated the specific components of social interaction that potentially drive advantages in learning. Future research should integrate neural measurements into more immersive, life-like settings that allow for real-time, responsive interaction with a social partner. Along these lines, Titone & Tiv6 recently proposed the “socially situated” Systems Framework of Bilingualism, whereby psycholinguists and cognitive neuroscientists are asked to “rethink experience”, going beyond individual learner abilities to thoroughly consider sociolinguistic and sociocultural experiences in understanding language and multilingualism as a whole. This is crucial for capturing the full complexity of socially interactive L2 learning as it unfolds in natural contexts, and for uncovering how such interactions shape underlying neurocognitive processes.

Word learning: a case study in socially interactive learning

Given the challenges and opportunities outlined above, it is important to explore new ways of advancing socially interactive L2 learning, both in theory and through innovative experimental set-ups. One illustrative sub-domain of L2 learning is word learning. While L2 language learning extends far beyond individual words, words are the natural starting point: they are the basic building blocks of comprehension and production and crucial contributors to linguistic fluency102. Social, embodied and multimodal learning might allow learners to more effectively integrate new words due to the richness of the semantic context, compared to word-meaning translation-type learning. Memory traces are reactivated after we encode and integrate new information that is semantically congruent with our existing knowledge, also known as conceptual schemas103. Considering that social contexts are a daily, familiar reality for most of us, they could represent “existing” knowledge within which a novel linguistic element is inserted during learning. Furthermore, using language for interacting with others binds processes related to perception, attention, memory, and emotion together104. The complexity of social environments and interactions could lead to deeper encoding of new linguistic content and hence long-lasting memory traces9. This effect pertains to the levels-of-processing hypothesis105, according to which memory encoding depends on the depth of processing required.

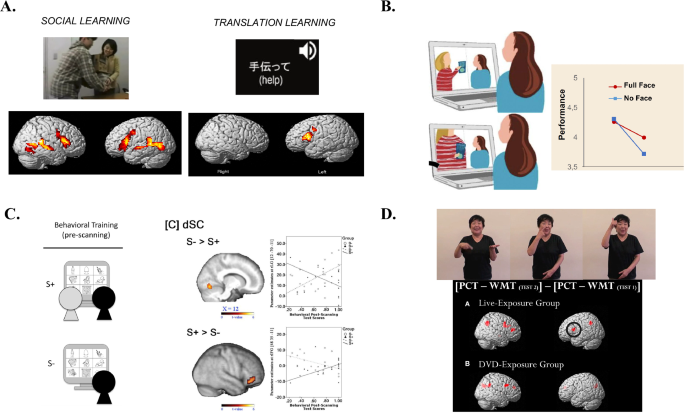

Following this reasoning, socially interactive L2 learning would ultimately allow for faster and more robust consolidation of associated information, such as the integration of new words into existing lexical-semantic networks106. The mental lexicon is generally conceptualized as consisting of two interconnected areas of representation: word form, encompassing a word’s phonological and orthographic characteristics, and word meaning, which refers to a word’s semantic associations with other words and its relationship to the real world107. A major question in the L2 literature is whether L2 lexicosemantic knowledge relies on the L1 lexicon to access meaning, or whether there is a direct connection between the L2 lexicon and meaning. The influential Revised Hierarchical Model108 (Fig. 2A) suggests that the L2 lexicon initially relies on L1 translations during early learning and later develops direct connections to conceptual meanings as proficiency increases. Initial supporting evidence came from translation tasks showing that L2 learners whose L1 was still dominant had greater difficulty translating from the L1 to the L2 than the other way around108,109.

However, L2 words may be represented as both lexical and conceptual entries, like L1 words, if acquired in environments where both form and meaning are emphasized110. By enriching the learning context, multimodal and socially interactive L2 learning environments could help L2 learners establish more direct connections between L2 words and concepts from the very beginning of L2 learning and bypass reliance on L1 translations. We propose an extension of the Revised Hierarchical Model, in which socially enriched contexts would facilitate the establishment of more direct links between L2 lexical items and conceptual representations compared to learning in classical non-social settings (Fig. 2B). Our model allows for the examination of how different aspects of social interaction (multimodal, embodied, interactive and social feedback factors) supports L2 word learning.

A The Revised Hierarchical Model (adapted from Kroll & Stewart, 1994, copyright permission from Elsevier, license number: 5956110535190). L1 and L2 words are interconnected via lexical and conceptual links. The lexical links are stronger from the L2 to the L1 than the other way around. Conceptual links are stronger for the L1 than for the L2. B Our proposed extension to the model: L2 learning in multimodal and social settings could form stronger links between L2 wordforms and concepts.

VR as a promising avenue for advancing research on socially interactive second language learning

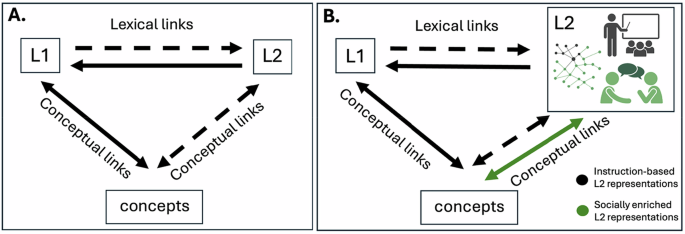

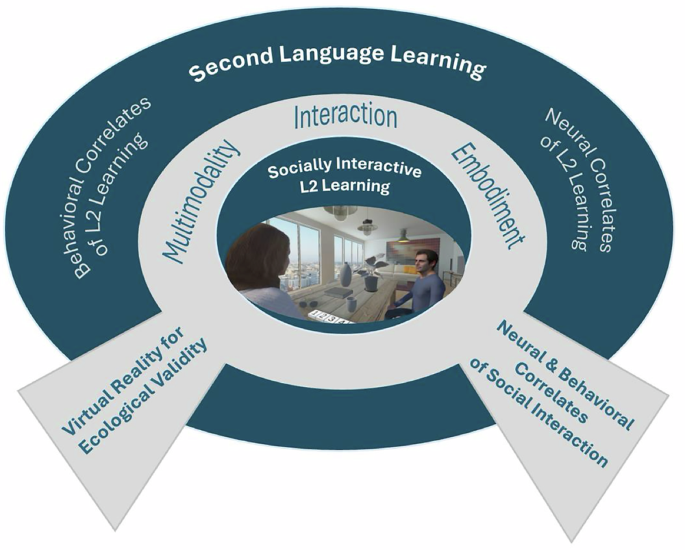

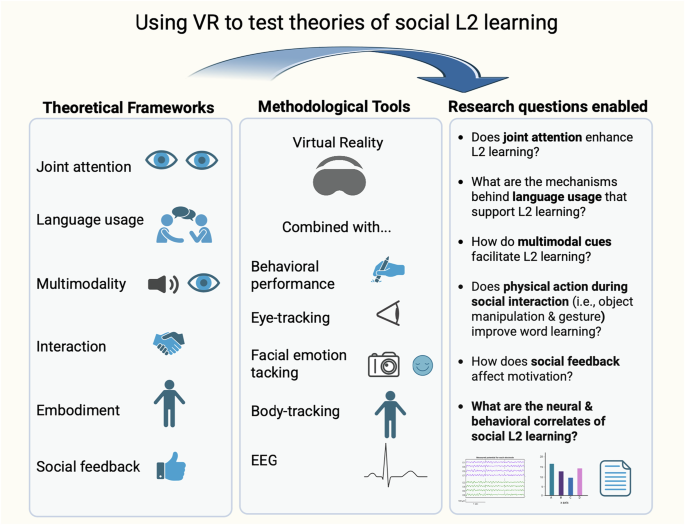

Taken together, the studies and theoretical frameworks reviewed here underscore the central importance of social interaction in L2 learning, while also revealing a significant gap in our understanding of the mechanisms that support it. This gap is largely due to the challenges of creating appropriate experimental settings15. Truly grasping how social interaction shapes L2 learning calls for experimental paradigms that bridge social interactions and appropriate, reliable behavioral and brain measures in highly controlled yet ecologically valid environments. We argue here that virtual reality (VR) offers exactly this methodological bridge. VR provides a much sought-after means of sufficiently engaging the sensorimotor system to elicit meaningful responses111, thus leading to findings that can generalize to real life47 (Fig. 3). In what follows, we review how VR can help us to make significant strides in understanding the role of social interaction in L2 learning.

Although VR cannot replace real human interactions, it is a powerful tool that can facilitate insights into social dynamics and interactions, even without perfect realism112,113. VR strives to replicate reality through three-dimensional environments with visual and auditory stimuli that often evoke a sense of presence in an immersive virtual world. Here, the concept of “presence” refers to the feeling of being in the virtual space and that events that are occurring there are truly occurring113,114. These environments afford interactions with both objects and social agents (i.e., virtual characters that interact with participants), which can bring experimental studies on language processing and learning much closer to a real-life experience. According to Peeters, VR “shifts the theoretical focus toward the interplay between different modalities […] in dynamic and communicative environments, complementing studies that focus on one modality in isolation”47. Not only are users perceptively immersed, but they can perform naturalistic actions and receive real-time feedback for these actions, whether it be manipulating objects or conversing with a social agent. Crucially, VR allows for the full control of multimodal sensory stimulation (i.e., the onset, location, and duration of presentation of the stimuli) to observe how specific visual and auditory input influences linguistic processes.

Though limited in number, studies that used virtual environments (VE) to investigate L2 learning have found an advantage for “embodied” learning in comparison with less contextual learning115,116,117. However, studies using VEs are limited in terms of visual immersion, physical interaction, and embodiment compared to VR studies that use head-mounted displays (HMDs)118. HMDs and Cave virtual environments (CAVEs) afford a heightened sense of embodiment by surrounding participants visually and enabling direct interactions via hand-held controllers, finger trackers, and hand-tracking. In the case of HMDs – now widely regarded as the immersive, affordable, and portable gold standard in VR research –, when participants are embodied in a virtual body, this provides them with a sense of body ownership and agency61. Recently, interactive VR strategies involving either an HMD or a CAVE have been combined with brain measures in a growing range of language studies71,119,120,121,122,123. Overall, these more immersive studies represent an important advance in observing the behavioral and neurocognitive substrates of situated and interactive language processing and learning. However, although these studies provide initial evidence in support of the idea that multimodal contextual cues and embodied processes can boost language processing and L2 learning, they lack a genuine social component. Indeed, most VR studies on L2 learning so far have focused on physical interaction with objects or environments but have not integrated meaningful social interactions. The absence of social agents capable of engaging in responsive communication within these environments leaves a significant gap in understanding how social factors shape L2 learning. Immersive VR studies offer a way forward: by surrounding participants visually and enabling naturalistic interaction, they provide a powerful means to investigate situated and socially grounded language learning under controlled conditions. In the remainder of this review, we use “virtual reality” (VR) to refer specifically to immersive experiences delivered via head-mounted displays (HMDs).

It is important to point out that there are clear limitations to using VR social agents as substitutes for real humans, particularly in the realm of language and multimodal communication. For instance, delivering high-quality, real-time language input, especially in the form of discourse, can be challenging. However, rapidly advancing AI technology is poised to make this possible in the near future. For experiments requiring complex behaviors such as negotiating meaning or providing corrective feedback, actors, confederates, or naïve participants should (continue to) be used. Indeed, humans provide cues during these activities that are extremely difficult to reproduce. On the other hand, numerous social cognition studies using VR have shown that fully replicating reality is not necessary for us to experience “real” feelings and display real-world behavior124. VR can convince us that something is happening (plausibility) and that we are in a particular place (place illusion)112,113,125,126.

Social paradigms that engage and manipulate simpler social, multimodal cues, along with environmental cues, could nevertheless provide the illusion of a real social interaction, representing significant potential to advance L2 learning studies. Again, these paradigms offer greater experimental control compared to using human counterparts. For instance, in VR, multimodal factors such as the speaking pace, accent, and prosody of a virtual agent can be altered while maintaining the same physical appearance (or vice versa). Additionally, the learning environment or the interlocuters’ physical appearance and behavior (i.e., social feedback such as smiling and nodding) can be finely altered to the desired degree. Moreover, VR design is rapidly advancing, creating interactive social agents modeled on humans who produce increasingly convincing facial and physical movement127. During L2 learning, key variables, such as agent gaze, feedback valence, and physical characteristics (e.g., age, gender), can be manipulated to examine their effects on learning outcomes. Moreover, virtual agents provide consistency that is difficult to achieve with human counterparts. As mentioned earlier, the second-person neuroscience approach calls for the examination of the neural correlates of two-person social interactions, which are shown to differ from those seen during social observation and to engage the ‘mentalizing network’94. Although VR social agents are not real humans, they can be perceived as social partners and engage similar processes as human-to-human interactions, contingent on visual, behavioral, and social factors126,128,129,130,131. For instance, direct gaze from a virtual agent was shown to engage reward networks132.

Beyond creating immersive and interactive environments, VR also enables the precise measurement of behavioral and psychophysiological responses during language learning. Performance-based metrics, such as response times and accuracy, along with self-report measures of engagement and motivation, offer insight into the effectiveness of different social teaching strategies. But VR goes further by allowing for the continuous tracking of learners’ movements and attentional dynamics. Through HMDs and hand controllers or hand-tracking systems, eye, head, hand, and body movements are recorded in real time, offering rich data on embodied and social behavior. Integrated eye-tracking systems, for instance, allow for the analysis of visual attention and joint attention, key mechanisms in social learning17, (e.g., by capturing when and how learners follow a virtual agent’s gaze). Subtle changes in learners’ facial muscle activity can also be measured via integrated cameras or sensors, enabling real-time emotion recognition during interactive learning tasks133,134. Social engagement can be quantified via body movement synchrony between learners and virtual teachers, a phenomenon linked to communicative success in L1 contexts135,136. Finally, communicative production can be recorded through metrics like hand movements and vocalizations47. Additional measures, such as heart rate, electrodermal activity, and speech or gesture patterns, provide further insight into the emotional and interactive dimensions of the learning experience. The combination of immersive social scenarios with high-resolution behavioral and physiological tracking renders VR an unparalleled methodological platform for investigating how social cues and interactions shape L2 learning processes.

How VR can be used to test socially grounded frameworks of second language learning

VR is particularly valuable as a tool for investigating the socially interactive L2 learning frameworks discussed in the first half of this review in that it allows us to manipulate a specific aspect of social interaction (e.g., social gaze, social feedback) while controlling other complex factors (e.g., the physical appearance and behavior of a social agent), facilitating replicability137 (Fig. 4). In line with joint attention dynamics widely studied in L1 acquisition, we recently combined VR and eye-tracking to examine whether gaze following supported L2 word encoding in adults. As an example, we taught participants novel L2 words with three different virtual teachers: a Good teacher (who gazed at the correct object while producing a word), a Bad teacher (who gazed at the incorrect object), and a Random teacher (who gazed at the correct or incorrect object, randomly) (Zappa et al., under review). All teachers provided reliable social feedback. Words learned with the Good teacher showed improved performance post-training, particularly when participants followed his gaze towards the correct object during learning. According to self-reports, participants were unaware of the manipulation. Thus, reliable referential gaze seems to boost the mapping between words and objects unconsciously, beyond feedback alone, mirroring joint attention mechanisms in L1 acquisition. These results demonstrate how eye-tracking in VR can reveal non-conscious learning mechanisms that would remain undetected in traditional behavioral studies. This type of manipulation would be very difficult to achieve in a controlled manner using actors or confederates who were physically present. Furthermore, using a flatscreen would take away from participants’ feeling of being in the same physical space as the agent (copresence), as well as that of looking at the same objects, in a shared physical space, essential for joined attention and life-like gaze following. Although immersive VR studies highlight the benefits of embodied interaction for L2 learning, few have tested contingent social cues like gaze or feedback. Our recent study is, to our knowledge, the first to do so, pointing to a promising direction for theory-driven research on social processes in language learning.

Second language acquisition (SLA) approaches align well with VR environments that could enforce iterative practice loops through contingent responses from virtual agents. VR also offers a unique opportunity to examine multimodal components both separately and in combination by manipulating visual (gestures, gaze), and auditory (prosody) cues produced by virtual agents. Regarding embodied processes during social interaction, learners can manipulate objects (i.e., hand an object to a social agent), see and perform gestures, and move through social environments as they process and acquire new words. VR also provides an ideal context to test social feedback as informational and affective reinforcement. Virtual agents can deliver precisely timed verbal and nonverbal feedback, such as praise, corrections, or facial expressions, in response to learner performance. These cues can be systematically varied in valence, modality, and contingency to investigate differences in learning outcomes and motivation. Further, our extension of the Revised Hierarchical Model108 (Fig. 2B) can be empirically tested using VR to compare word learning outcomes across socially enriched and more traditional learning contexts. Virtual agent referential gaze or gestures, and both agents and learners’ interaction with objects can be manipulated while linguistic input remains strictly controlled.

A potentially crucial yet under-studied aspect of socially interactive second language learning are individual differences in willingness to communicate (WTC), or how likely a speaker is to engage in oral communication138. Conceived as a dynamic construct shaped by both personality traits and context-sensitive variables139,140,141, WTC is clearly influenced by established social dynamics142 and inherent social rewards. It therefore represents an important factor when examining how motivation impacts L2 learning38,143. While it can be viewed as an individual trait (proneness to speak after learning), it can also vary over time, or according to learning situations144. Ties between social interaction, learning motivation, and WTC make it an excellent candidate to study in conjunction with L2 learning in socially interactive environments. Using virtual social agents, future studies could measure the impact of different social learning scenarios, instructors, and feedback on WTC, L2 learning motivation, and learning success. Importantly, within such environments, we can assess how learners’ communicative intent is modulated by specific features of interaction, for example, whether contingent feedback or perceived agent cooperativeness increases or decreases WTC over time. In addition, VR enables the collection of fine-grained behavioral and physiological data (e.g., gaze patterns, facial emotions, speech onset latencies, body orientation), offering converging measures of learners’ social engagement and readiness to initiate communication (Fig. 4).

The blue, outer circle of this figure describes different measures that can be used to examine L2 learning studies: behavioral and neural. The grey, inner circle lists three components of L2 learning in a social environment: multimodality, interaction, and embodiment. The left-hand side grey ray represents the benefit of virtual reality for examining socially interactive L2 learning, and the right-hand side ray, that of taking into account neural and behavioral correlates of social interaction in such studies. Finally, the inner blue circle shows a socially interactive L2 learning VR environment with two social agents – one represents the participant and the other an interactive virtual partner. The human characters in this figure are AI-generated.

Illustration of how immersive VR, combined with behavioral and neurophysiological tools, enables targeted testing of core mechanisms proposed in socially grounded L2 learning theories. Created in BioRender. Zappa, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/n8mobrf.

In all of the above examples, behavioral, psychophysiological (i.e., eye-tracking, facial emotion recognition), and neural responses can reveal how different aspects of social interaction shape L2 learning. VR is particularly well-suited to investigating the brain mechanisms underlying socially grounded L2 learning. As mentioned earlier, neural measures allow us to observe L2 learning phenomena that might not be measurable behaviorally, including semantic processing, syntactic processing, reward processes, feedback expectation and processing, and inter-subject correlation (when more than one learner is involved). One straightforward way to test the effect of socially interactive learning is to measure brain activity using EEG or fMRI during language processing before and after immersive VR learning sessions (compared to a control condition), to measure changes induced by learning71,119. Although more challenging to set up, EEG can be directly measured while participants wear an HMD headset, as long as they remain seated and movement is limited during critical time windows, to avoid artifacts. It is crucial to measure the neural correlates of socially interactive L2 learning during the learning tasks themselves. EEG is especially valuable for studying how language learning unfolds in real time, as brain activity is captured with excellent temporal resolution that matches incredibly rapid language computations. Also, social reward, defined as positive verbal or non-verbal experience such as praise, smiling, or encouraging145 has been linked to attentional bias146 and improved learning but has not yet been investigated in connection with L2 learning with social partners. Importantly, although EEG-derived measures associated with processes related to socially interactive L2 learning have been studied, such as beta synchronization as a marker of reward147 or inter-brain synchrony as a marker of shared attention and engagement98,99,148, to our knowledge no studies have employed these measures during socially interactive L2 learning in ecologically valid environments. Using VR to present learners with realistic, immersive, social experiences while acquiring brain and behavioral measures of social interaction and L2 learning yields a novel avenue of ecologically valid, yet controlled, L2 learning research.

Applications

While this review has emphasized VR as a tool for fundamental research, experimental advances in how social interaction impacts L2 learning are likely to inform innovations in instruction and rehabilitation. Knowledge about how learners respond to social cues and dynamics can inform the design of instructional strategies that promote active engagement with responsive interlocutors. It can also enrich language rehabilitation strategies. For example, people with aphasia show considerable variability in their ability to relearn words68,149,150. While this is often attributed to lesion differences, interaction itself may serve as a crucial motivational and contextual support. It has been shown that incorporating meaningful communication into therapy is more effective than traditional production-based methods alone151. Interaction-based paradigms in VR, such as those involving multimodal cues and real-time feedback, could therefore offer a promising avenue for the development of more engaging and responsive rehabilitation protocols. Similar opportunities arise in autism research. A recent study by De Felice et al.93 found that both autistic and neurotypical adults learned concepts most effectively during live interactive sessions, compared to observing recorded interactions or watching a monologue. Enjoyment was also highest in the interactive condition and strongly predicted learning outcomes. These findings suggest that social engagement can support learning even in populations typically considered less responsive to social cues. Transferring such paradigms to immersive VR would allow researchers to systematically manipulate degrees of co-presence, interactivity, and responsiveness, offering new insights into the role of social dynamics in learning across neurodiverse populations. In sum, research on word learning with social interaction can significantly advance both our theoretical understanding of L2 learning and the development of personalized, socially responsive teaching and rehabilitation strategies.

Conclusion

Given the central function that social interaction plays in language, this aspect could, in turn, significantly affect how an L2 is learned. Although the literature shows an increasing interest in this facet of L2 learning, researchers are often met with the challenge of providing learners with ecologically valid, socially interactive environments in which to examine the social component of L2 learning. Beyond offering a new methodological tool, VR provides a means to empirically test and refine existing theories of L2 learning. By isolating and manipulating factors such as joint attention, social feedback, embodiment, and multimodal input, VR can help to reveal which social mechanisms underlie comprehension and learning, thereby sharpening current theoretical accounts. Teaching participants an L2 via highly engaging virtual social agents makes it possible to measure when and how particular aspects of social environments and interactions modify or enhance L2 learning. This integration is not merely hypothetical – recent studies have already begun to demonstrate the feasibility and scientific value of using VR to examine these learning frameworks. Looking ahead, the combination of VR with neurophysiological and psychophysiological measures opens exciting possibilities for examining how social engagement influences language encoding and consolidation in real time. As adaptive, AI-driven virtual agents become increasingly sophisticated and capable of contingent dialog, they will offer unprecedented opportunities to investigate how motivation, social reward, and communicative alignment unfold during L2 learning. VR is not a mere technological upgrade; it represents a paradigm shift. Ultimately, this shift may enable a deeper understanding of the cognitive and neurocognitive mechanisms that underlie L2 learning in social contexts, refining and empirically grounding our proposed extension of the Revised Hierarchical Model (Fig. 2B). By enabling experimental control without sacrificing ecological validity, this line of research opens the door to a more complete science of L2 learning: one that finally captures the social, dynamic nature of how languages are truly learned.

link